Fine Art Photography

fine art photography

fine art photography

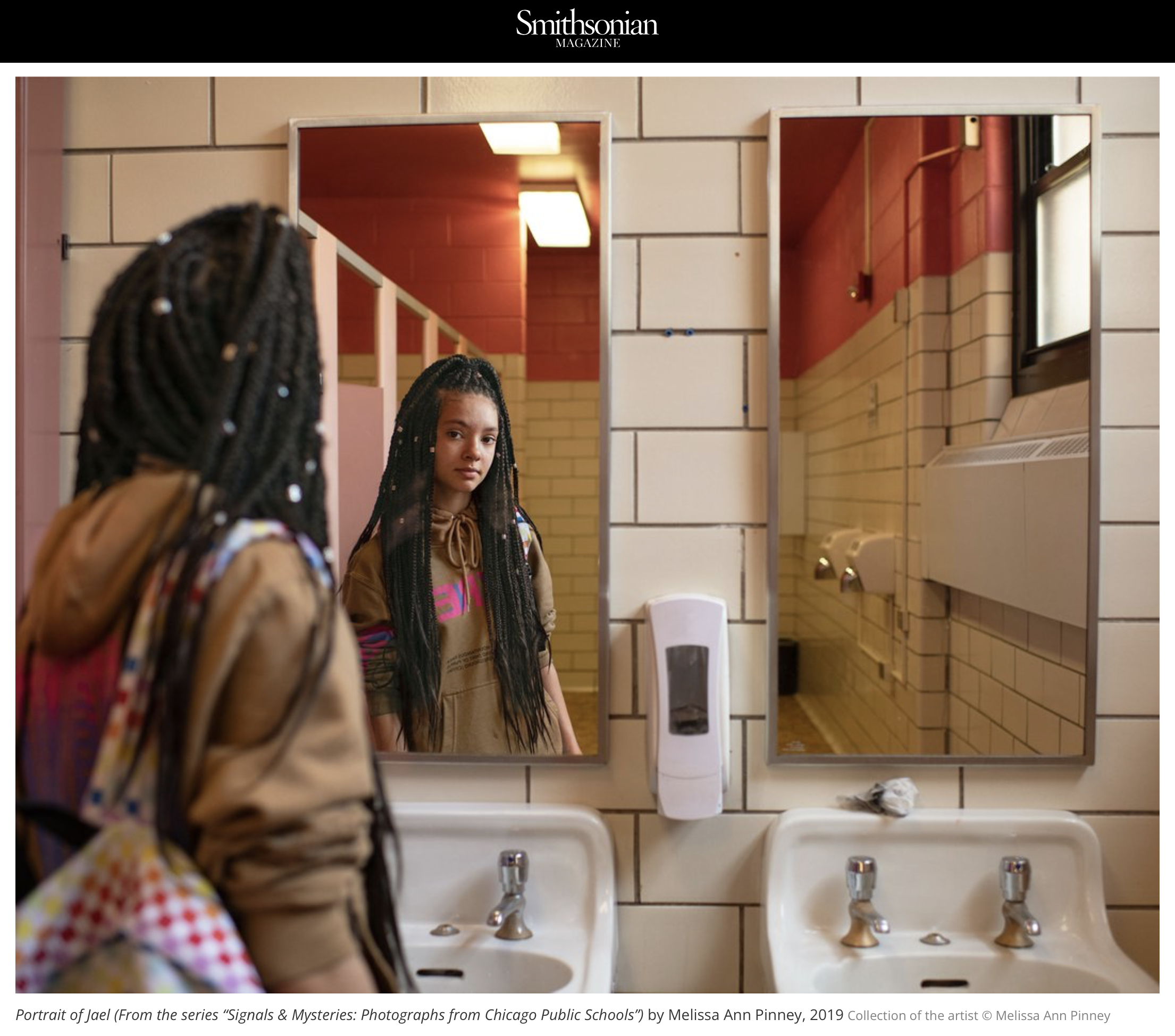

In Their Own Light: Photographs from Chicago Public Schools is about young people and their exploration of identity emerging through friendships, school traditions, and mourning rituals. Students define themselves, having grown up as heirs to the Black Lives Matter movement, #MeToo and an insistence on gender fluidity. My seven-year artist residency in Chicago Public Schools, began in a largely White elementary school and expanded to several predominately Black and Latinx high schools. In 2018, I had no idea of what was to come. The project evolved and shifted as I found new opportunities to deepen connections with students through a global pandemic, escalating racial and gender inequities and continuing gun violence.

I started work on this series under the auspices of Artists in Public Schools, a nonprofit arts organization founded by Suzette Bross, which pairs artists with Chicago Public Schools to tell individual stories of the public school system. I started at Bell School, located on the north side, which is well-resourced and serves neighborhood, deaf and gifted students. Bell has two recess periods a day, and cell phones are prohibited, freeing the students to run, climb and make up their own games on the fly. I learned to anticipate that energy, to be open to what is ordinarily unnoticed, and look to the periphery rather than the spotlight. I am grateful both for the privilege and the challenge of making pictures amid such inventive vitality.

In 2019, I exhibited my Bell School pictures for the first time at a local library; word of the project spread among parents and CPS administrators. As a result I was invited to document the historic merger of two racially and economically segregated schools located in the former Cabrini-Green housing area. I went into the newly created Ogden-Jenner Middle School naively, uninformed about the area and the history of the school merger aside from media accounts whose bias was not yet apparent to me.

The change of schools presented new challenges. Chicago is a notoriously segregated city, and Evanston, where I grew up, is still equally so. The Black and White kids in the Catholic schools I attended did not mingle and rarely socialized. Historic redlining and pervasive racism defined Evanston neighborhoods. Now, working in a school of predominantly Black students, I felt clueless and very White, ignorant of the student’s shared history, culture, language and references. From this starting place, I knew only to return each week to get to know the students and try to earn their trust. Over time, I did get to know and continued to photograph a group of students who went on to the Ogden High School and graduated recently. My worldview and assumptions shaped when I grew up are challenged again and again by the students I meet.

There were technical challenges too— I wasn’t happy with the quality of my photographs. I made pictures anyway—pictures the students asked me to make as they passed in the hallways or on the playground while posing in groups of friends. After each exposure the students would gather close to view the images on the back of my camera, telling me which ones they liked and using their phones to capture the images to share with friends.

I realize that my photographing in settings where the majority of students are Black and Brown can be seen as problematic. Yet this project has a direct relationship to my earlier work, work that revolved for decades around my daughter, Emma, and themes of young people at school and play. That series swirled out from our family life— Emma’s classmates and friends at school to our church, sports and social gatherings. There was tremendous support—everybody in the community knew who I was and knew of my work. Although the themes and events were similar, it was not my community or my child’s friends at Ogden; I had to find a different way into the work. Five years later I can say that I did find support, permission and collaboration among the students, especially the students I first met in middle school or ninth grade. Now the high school students see my work on Instagram and communicate with me by text to send them their portraits.

My work at Ogden-Jenner opened the door for me to photograph at Ogden International High School, where I worked through 2022. In 2021 I received the Diane Dammeyer Fellowship in Photographic Arts and Social Issues to complete my work at both of the Ogden Schools and begin to photograph at Senn High School, which is ongoing.

By continuing to show up and offer pictures to both individual students and the schools where I’ve worked, I have been welcomed generously. Now students ask me to photograph their sports events and performances, to document their birthdays and parties. In this way I hope to acknowledge and thank those who have given so much of themselves to the project.

The longer I do this work the more rewarding it has become for me personally as well as a photographer. One of the most unexpected gifts is realizing how much the students value the photographs. As Ogden student, Khov’ya, said, “I’m really happy you took those pictures. They might have seemed like regular days, but it’s good to look back on those moments…little memories and little moments. We just knew that you were always here, taking pictures.”

—Melissa Ann Pinney

February 2025

I made the first the Cellar Door picture in May, 2001, as a homage to the famous Alfred Steiglitz portrait of Georgia Engelhard. We had just celebrated Emma’s sixth birthday with a party in the backyard. Emma climbed up on the old cellar door; I was reminded of Steiglitz's photograph... and so it began.

It wasn’t until a year had gone by that I thought to continue the series, at first once a year and then once every season or so. Emma is now twenty-one years old and the photographs span more than a decade. We see Emma grow as the state of the house and garden change with her. My subjects here are emerging feminine identity, memory andthe passage of time. I asked Emma about her experience of the series and her response was a revelation to me.

Emma writes: "Over the years, my mom persuaded me with various incentives to climb up onto the cellar door to take photos; I remember resisting and arguing with her every time. I am grateful that she didn’t give up or give into my protests, especially during my angsty teenage years. Now when I look at the Cellar Door series I finally see what she always saw— a unique, meaningful compilation of my childhood and how I became the woman I am today. I remember who I was when she captured every image and why I chose each outfit for the series. When I look back on the Cellar Door Series I see the beginning of my love for sports that continues to this day; the comfort I felt as a “tomboy” skater girl at Montessori school; the intense pressure to act feminine and heterosexual at Catholic middle school; several stages in the battle against my eating disorder; and my slow acceptance of my lesbian identity. Individually, each Cellar Door image evokes touching memories, yet the beauty of my Mom’s vision lies within the series' collective power to reveal my personal growth and experience in a profound way."

The series, Girl Ascending, began with my photograph of a girl seemingly suspended in mid-air, holding onto a chain-link fence with one hand, her dress lifted by the breeze. The circumstances are commonplace: a baseball game, nondescript buildings and a dirt field seen through the fence. Nevertheless, the improbable levitation and serene demeanor of the girl suggested the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary to one, raised, as I was, on the symbolic imagery of Catholicism. I am interested in the passage of time, the cycle of the seasons, girls’ friendships and their ties to the elders who guide them. The images that most intrigue me are epiphanies, in which the ordinary reveals an underlying significance.

This project focuses on a touchstone moment in the lives of American women and girls: their emergence from protected youth to public maturity. From a core series of photographs of my daughter, Emma, the project has swirled out though friends and classmates, past their families, neighborhoods, social rituals, and community lives to develop a study of emerging female identity with all its promises and perils.

My mother, at seventy years old, told me that every time she looked in the mirror she wondered who "that old bat" was looking back. In her mind’s eye she still had the face she had at eighteen. This, after eight children and forty years of marriage. The photographs in Regarding Emma: Photographs of American Women & Girls explore both the persistence of the child-in-the-woman and the early cultivation of the woman- in-the-child. Girlhood may be understood as a part of a continuum that women revisit regardless of age.

Before our child was born nineteen years ago, it was generally understood among friends and family that the baby would be a girl. After all, women had been the subject of my work for many years. This happy coincidence of biology and feminism presented me not only with Emma, a daughter I cherish, but with new opportunities for making pictures as well. When I began the series Feminine Identity in 1987, I focused mostly on adult women. Now the scope of my work has widened to more often include men as fathers, grandfathers, husbands and brothers. But in photographing my own daughter and our family life together - in regarding Emma day by day- it has become clear that the heart of the project lies in images of girlhood.

TWO (Harper Design; On Sale April 14, 2015; $29.99) is an exquisite collection of captivating and thought-provoking photographs by award-winning photographer Melissa Ann Pinney that contemplate the essence of duality in our relationships and in the world that surrounds us. Pinney, whose work is in the permanent collections of dozens of American museums, including the Metropolitan, MoMA, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Getty, aims her lens at pairs—mostly, but not always human—that display or imply elusive connections of mind, of spirit, or of simply the act of being.

Edited and introduced by Pinney’s friend, New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett, the volume is filled with memorable images that encase rich stories: two children at play, a pair of aging friends, parent and child, couples in love. But deeper meanings can lurk in the margins of the frame, in the expressions in the eyes, in the disconnect of the connection. Photographs without human subjects bear their own mysteries: two nesting tea cups, an indoor pool, two chairs in autumn.

Patchett, whose enthusiasm for Pinney’s vision helped bring this project to fruition, has paired the photographs with remarkable essays about the nature of two, commissioned from some of the best writers at work today: Edwidge Danticat, Barbara Kingsolver, Richard Russo, Elizabeth Gilbert, Susan Orlean, Alan Gurganus, Maile Meloy, Elizabeth McCracken, Jane Hamilton, and Billy Collins (who provides a beautiful poem celebrating “two creatures bound by wonderment.”)

“I’ve always been interested in watching people together. I wonder what their story is, who they are to each other,” Pinney writes in the preface. “”No matter how uninspired I feel, how dull I think a place is, when I look at the world through a camera a new beginning takes place.”

Filled with startling, sensitive images and nuanced prose, TWO is an illuminating keepsake of human experience, at once universal and unique.