fine art photography

In Their Own Light: Photographs from Chicago Public Schools is about young people and their exploration of identity emerging through friendships, school traditions, and mourning rituals. Students define themselves, having grown up as heirs to the Black Lives Matter movement, #MeToo and an insistence on gender fluidity. My seven-year artist residency in Chicago Public Schools, began in a largely White elementary school and expanded to several predominately Black and Latinx high schools. In 2018, I had no idea of what was to come. The project evolved and shifted as I found new opportunities to deepen connections with students through a global pandemic, escalating racial and gender inequities and continuing gun violence.

I started work on this series under the auspices of Artists in Public Schools, a nonprofit arts organization founded by Suzette Bross, which pairs artists with Chicago Public Schools to tell individual stories of the public school system. I started at Bell School, located on the north side, which is well-resourced and serves neighborhood, deaf and gifted students. Bell has two recess periods a day, and cell phones are prohibited, freeing the students to run, climb and make up their own games on the fly. I learned to anticipate that energy, to be open to what is ordinarily unnoticed, and look to the periphery rather than the spotlight. I am grateful both for the privilege and the challenge of making pictures amid such inventive vitality.

In 2019, I exhibited my Bell School pictures for the first time at a local library; word of the project spread among parents and CPS administrators. As a result I was invited to document the historic merger of two racially and economically segregated schools located in the former Cabrini-Green housing area. I went into the newly created Ogden-Jenner Middle School naively, uninformed about the area and the history of the school merger aside from media accounts whose bias was not yet apparent to me.

The change of schools presented new challenges. Chicago is a notoriously segregated city, and Evanston, where I grew up, is still equally so. The Black and White kids in the Catholic schools I attended did not mingle and rarely socialized. Historic redlining and pervasive racism defined Evanston neighborhoods. Now, working in a school of predominantly Black students, I felt clueless and very White, ignorant of the student’s shared history, culture, language and references. From this starting place, I knew only to return each week to get to know the students and try to earn their trust. Over time, I did get to know and continued to photograph a group of students who went on to the Ogden High School and graduated recently. My worldview and assumptions shaped when I grew up are challenged again and again by the students I meet.

There were technical challenges too— I wasn’t happy with the quality of my photographs. I made pictures anyway—pictures the students asked me to make as they passed in the hallways or on the playground while posing in groups of friends. After each exposure the students would gather close to view the images on the back of my camera, telling me which ones they liked and using their phones to capture the images to share with friends.

I realize that my photographing in settings where the majority of students are Black and Brown can be seen as problematic. Yet this project has a direct relationship to my earlier work, work that revolved for decades around my daughter, Emma, and themes of young people at school and play. That series swirled out from our family life— Emma’s classmates and friends at school to our church, sports and social gatherings. There was tremendous support—everybody in the community knew who I was and knew of my work. Although the themes and events were similar, it was not my community or my child’s friends at Ogden; I had to find a different way into the work. Five years later I can say that I did find support, permission and collaboration among the students, especially the students I first met in middle school or ninth grade. Now the high school students see my work on Instagram and communicate with me by text to send them their portraits.

My work at Ogden-Jenner opened the door for me to photograph at Ogden International High School, where I worked through 2022. In 2021 I received the Diane Dammeyer Fellowship in Photographic Arts and Social Issues to complete my work at both of the Ogden Schools and begin to photograph at Senn High School, which is ongoing.

By continuing to show up and offer pictures to both individual students and the schools where I’ve worked, I have been welcomed generously. Now students ask me to photograph their sports events and performances, to document their birthdays and parties. In this way I hope to acknowledge and thank those who have given so much of themselves to the project.

The longer I do this work the more rewarding it has become for me personally as well as a photographer. One of the most unexpected gifts is realizing how much the students value the photographs. As Ogden student, Khov’ya, said, “I’m really happy you took those pictures. They might have seemed like regular days, but it’s good to look back on those moments…little memories and little moments. We just knew that you were always here, taking pictures.”

—Melissa Ann Pinney

February 2025

In Their Own Light: Photographs from Chicago Public Schools is about young people and their exploration of identity emerging through friendships, school traditions, and mourning rituals. Students define themselves, having grown up as heirs to the Black Lives Matter movement, #MeToo and an insistence on gender fluidity. My seven-year artist residency in Chicago Public Schools, began in a largely White elementary school and expanded to several predominately Black and Latinx high schools. In 2018, I had no idea of what was to come. The project evolved and shifted as I found new opportunities to deepen connections with students through a global pandemic, escalating racial and gender inequities and continuing gun violence.

I started work on this series under the auspices of Artists in Public Schools, a nonprofit arts organization founded by Suzette Bross, which pairs artists with Chicago Public Schools to tell individual stories of the public school system. I started at Bell School, located on the north side, which is well-resourced and serves neighborhood, deaf and gifted students. Bell has two recess periods a day, and cell phones are prohibited, freeing the students to run, climb and make up their own games on the fly. I learned to anticipate that energy, to be open to what is ordinarily unnoticed, and look to the periphery rather than the spotlight. I am grateful both for the privilege and the challenge of making pictures amid such inventive vitality.

In 2019, I exhibited my Bell School pictures for the first time at a local library; word of the project spread among parents and CPS administrators. As a result I was invited to document the historic merger of two racially and economically segregated schools located in the former Cabrini-Green housing area. I went into the newly created Ogden-Jenner Middle School naively, uninformed about the area and the history of the school merger aside from media accounts whose bias was not yet apparent to me.

The change of schools presented new challenges. Chicago is a notoriously segregated city, and Evanston, where I grew up, is still equally so. The Black and White kids in the Catholic schools I attended did not mingle and rarely socialized. Historic redlining and pervasive racism defined Evanston neighborhoods. Now, working in a school of predominantly Black students, I felt clueless and very White, ignorant of the student’s shared history, culture, language and references. From this starting place, I knew only to return each week to get to know the students and try to earn their trust. Over time, I did get to know and continued to photograph a group of students who went on to the Ogden High School and graduated recently. My worldview and assumptions shaped when I grew up are challenged again and again by the students I meet.

There were technical challenges too— I wasn’t happy with the quality of my photographs. I made pictures anyway—pictures the students asked me to make as they passed in the hallways or on the playground while posing in groups of friends. After each exposure the students would gather close to view the images on the back of my camera, telling me which ones they liked and using their phones to capture the images to share with friends.

I realize that my photographing in settings where the majority of students are Black and Brown can be seen as problematic. Yet this project has a direct relationship to my earlier work, work that revolved for decades around my daughter, Emma, and themes of young people at school and play. That series swirled out from our family life— Emma’s classmates and friends at school to our church, sports and social gatherings. There was tremendous support—everybody in the community knew who I was and knew of my work. Although the themes and events were similar, it was not my community or my child’s friends at Ogden; I had to find a different way into the work. Five years later I can say that I did find support, permission and collaboration among the students, especially the students I first met in middle school or ninth grade. Now the high school students see my work on Instagram and communicate with me by text to send them their portraits.

My work at Ogden-Jenner opened the door for me to photograph at Ogden International High School, where I worked through 2022. In 2021 I received the Diane Dammeyer Fellowship in Photographic Arts and Social Issues to complete my work at both of the Ogden Schools and begin to photograph at Senn High School, which is ongoing.

By continuing to show up and offer pictures to both individual students and the schools where I’ve worked, I have been welcomed generously. Now students ask me to photograph their sports events and performances, to document their birthdays and parties. In this way I hope to acknowledge and thank those who have given so much of themselves to the project.

The longer I do this work the more rewarding it has become for me personally as well as a photographer. One of the most unexpected gifts is realizing how much the students value the photographs. As Ogden student, Khov’ya, said, “I’m really happy you took those pictures. They might have seemed like regular days, but it’s good to look back on those moments…little memories and little moments. We just knew that you were always here, taking pictures.”

—Melissa Ann Pinney

February 2025

Jael, Ogden International High School. 2019

Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Senn Arts High School. 2022

Zydrea, Brooklyn, Akylah & Friends, Ogden-Jenner Middle School. 2019

Softball, Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

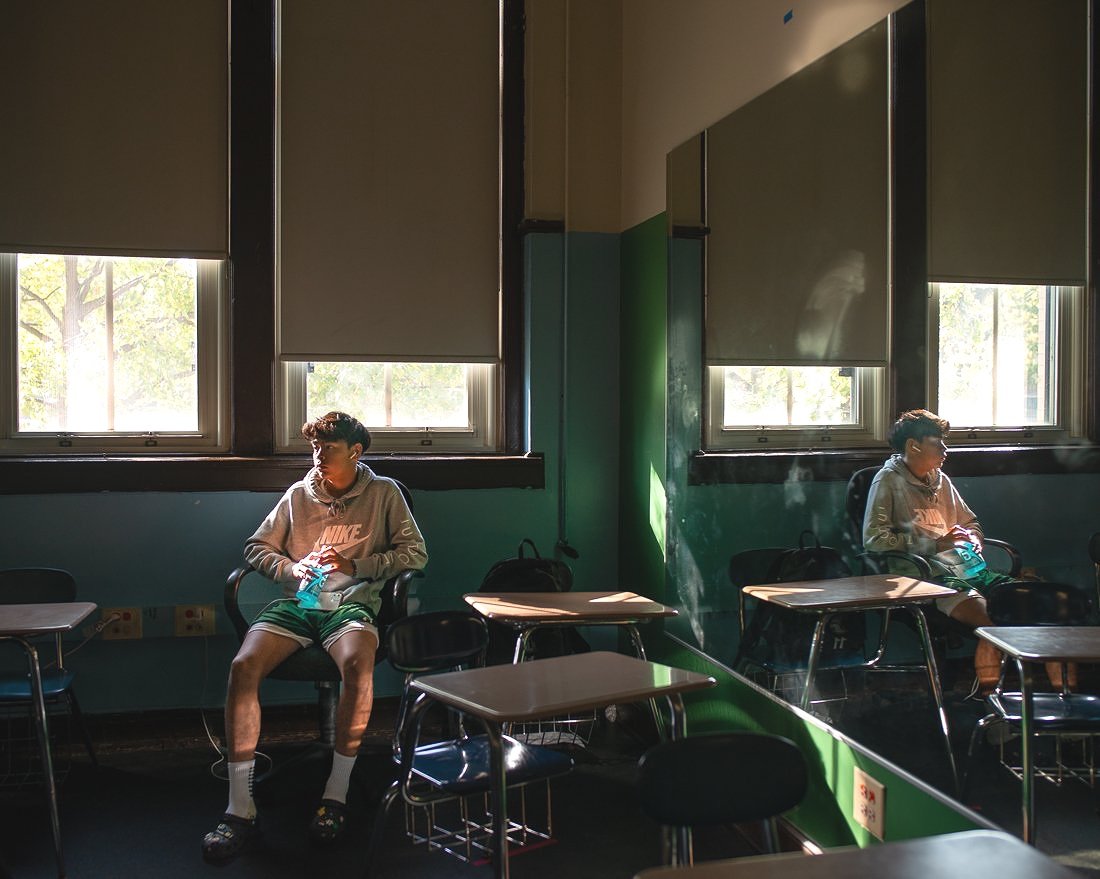

Ogden International High School. 2024

Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Bell School. 2020

Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Nicholas Senn High School. 2022

Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Jakolbi Lard, d.2022, Ogden International High School. 2019

Pride Day, Nicholas Senn High School. 2022

DeJa Rae Reaves, d.2023, Ogden International High School. 2022

Senn v. Ogden Softball Game at Senn High School. 2024

Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Baseball Game, Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Football Practice, Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Dismissal, Nicholas Senn High School. 2022

Ogden International High School. 2019

18th Birthday, Nicholas Senn High School. 2023

Soccer Meeting, Nicholas Senn High School. 2022

Senn Arts High School. 2024

Prom Send-Off, Ogden International High School. 2022

Brothers, Nicholas Senn High School. 2024

Prom, Ogden International High School. 2023

Graduation, Ogden International High School. 2022

Dismissal, Nicholas Senn High School. 2022